Secrets of a 400-Year-Old shipwreck

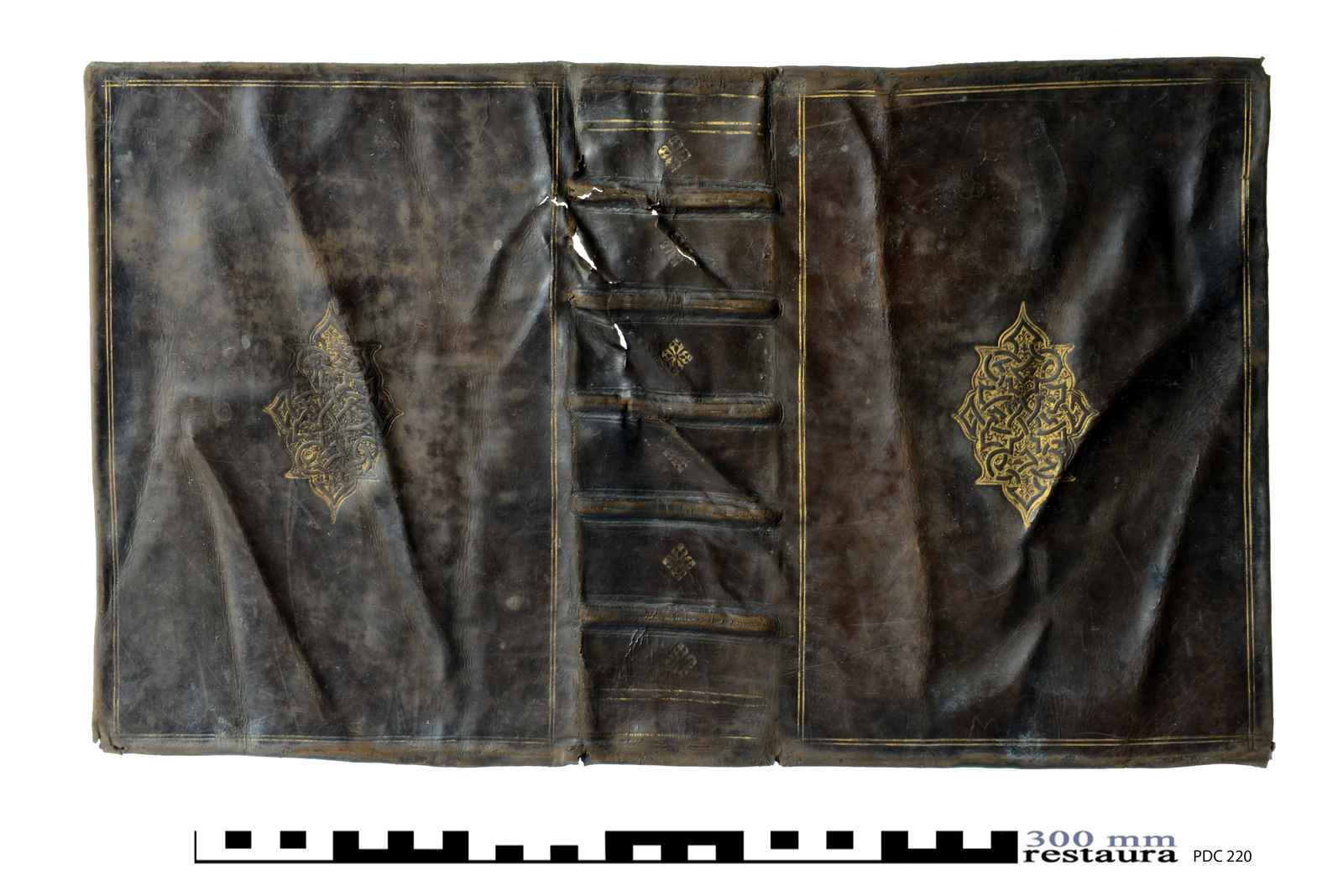

In 2014, a group of hobby divers found a shipwreck near the island of Texel, off the coast of the Netherlands. The ship, which was upright on the sea floor, had been there since the 1640s or 1650s, and contained a cargo that ranged from ship’s equipment to luxurious women’s clothing. Most tantalisingly, one chest contained a pile of 32 leather book bindings. (Another four books exist in ‘ghost’ form, because their binding has imprinted on the other books in the wreck.) The pages had long disintegrated, but the bindings contained secrets just waiting to be unlocked.

The person to undertake that job was Dr Janet Dickinson, a Senior Associate Tutor with the Department. As part of a team led by academics at the Universities of Amsterdam and Leiden, Dickinson worked on the bookbindings for a year, an experience she describes as ‘absolutely fascinating’. A novice to the field herself (Dr Dickinson’s own specialty is the cultural and political history of early modern England and Europe), she has consulted extensively with book bindings experts. ‘It is amazing what you can find out just from having these leather covers with the decoration on them, which enable you to give them loose geographical points of origin, and potentially loose dates as well,’ she says. (A small number, she adds, have the dates on them.) The bindings all precede the period when titles were added, so we don’t know what the books might have contained.

A royal connection?

Because one of the bindings has the Stuart royal coat of arms on it, Dr Dickinson initially thought that the book might have come from the collection of Charles I. Having visited the collection of royal books held in Oxford’s Worcester College, however, she realised that that wasn’t the case. She then consulted the world expert on early seventeenth century English book bindings, who identified it as a trade binding - a binding put on a book to sell it.

A chance meeting with a royal librarian at a symposium led to Dr Dickinson visiting the library at Windsor Castle where she found a precise match for one of the symbols used on two of the bindings, along with another example at the University of Cambridge. ‘This is such a magical thing, because you have this book under the water for 400 years, and suddenly you’re finding that somebody has used the exact same tool on all three of these books,’ she says. ‘That’s like a needle in a haystack.’

So how can we be sure that the books didn’t belong to royalty? The level of quality simply isn’t there, says Dr Dickinson. If a book wasn’t intended to be presented to royalty, ‘the point of a binding in this period is utility.’ Although some customers were becoming interested in personalising the bindings, the main purpose of a binding was simply to hold the book together and ‘look reasonably decent’, which is what we have in the Texel collection.

A tangible connection with the past

Only a small number of the bindings came from England, with most coming from Germany or the Netherlands. One book that was stamped with a family coat of arms turned out to come from the Ostrogski family in Poland. Another binding, which included a crucifixion scene as part of the decoration, was an exact match for a binding in Munich.

The books almost certainly belonged to a well-off family, she says, though probably not nobility: ‘These are good quality books. A lot of them have traces of gilding, so they looked amazing when they came out of the water, glowing with this gold coming into view, and that’s a sign of value. Somebody has paid money to have not just the decoration put on, but to have it gilded.’ There are also signs of how the books were used. One she particularly likes – a high-quality French binding – has a bird doodled in the corner, probably by a child.

For Dr Dickinson, the project has represented a particularly exciting opportunity to do a different kind of historical research, one that required collaboration with experts such as Philippa Marks, a curator and bookbindings specialist at the British Library: ‘It was an amazing revelation for me how generous people were.’ It was also enjoyable to do research that provided a tangible link to the past, she says: ‘It’s a magical thing when you hold these books in your hand and realise that the last time someone touched them was when they put them into the chest to travel.’

Numerous questions remain unanswered, however. Dr Dickinson thinks it’s possible that the books were purchased second-hand, so they could represent someone’s personal library. It could also be a collection of books for sale, though she thinks that is less likely. Another mystery relates to the initials TG found on the book that used the Stuart arms binding. Who could they belong to? If you have any suggestions, she would like to hear from you.

Dr Dickinson’s involvement in the research is now over, and she has been giving talks on the research as well as writing a paper for publication. Research on the 1,000 items found in the shipwreck continues, however, and there are plans for an exhibition in Texel’s Shipwreck and Beachcombing Museum. So she may have an opportunity to return to the mysteries of the bookbindings: ‘It’s a big tourist draw on the island and I'd love to be involved in that.’

Find more information on our website about Dr Janet Dickinson and her upcoming short courses.

Published 11 July 2019