Classical architecture, principles and foundations

1.2 The classical orders

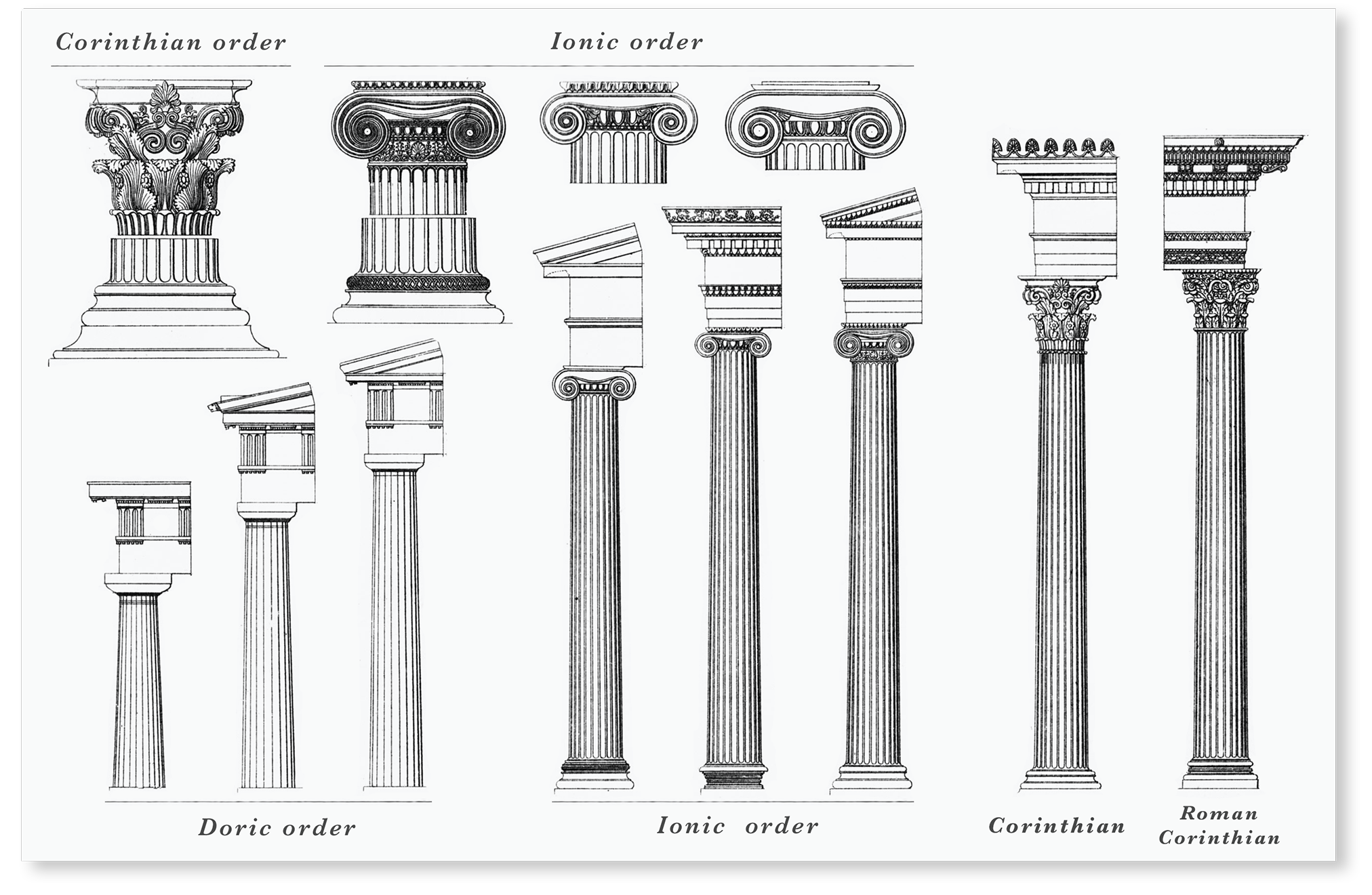

The use of the different orders is central to classical architecture, and to the later styles which drew upon it. Now that you have read Sutton, test your knowledge of the orders with the following questions:

Individual activity: Quick test

In simple chronological terms, in what sequence did the orders first appear? Answer

As Sutton says (p. 13) the Doric and Ionic orders appear to have emerged first – in mainland Greece and Asia Minor, respectively (there is still much uncertainty as to the precise early history of these architectural forms). As Sutton goes on to say, the Corinthian order seems to have appeared rather later – and indeed is more characteristic of Roman, than of Greek, architecture.

Briefly describe the main formal characteristics of each of the three main orders. Answer

Essentially, the Doric order is the most massive of the three. Its (usually fluted) columns are comparatively short, relative to their height. The column capitals of the Doric order are plain and unadorned in form - and the Doric entablature is likewise severe and unadorned, its decoration being typically limited to triglyphs and metopes (see Sutton, p. 13, and p. 373). It should be pointed out that, as Sutton says on p. 14, ‘By the 5th century Doric temples had become standardised and extremely refined... [such that] Many of these refinements are detectable only by careful measurement.’ One typical Doric refinement that is clearly visible is the use of 'entasis' on columns, whereby the column shaft tapers slightly toward the top, so as to create a more pleasing perspective when viewed from ground level. This can be seen in its crudest form in the columns of the temple at Paestum (illustrated on p. 11), and in more subtle form in the columns of the Parthenon (illustrated on p. 12).

The Ionic order is more slender overall: its columns are taller relative to their height. The Ionic capital typically employs twin volutes, and the Ionic entablature eschews triglyphs and metopes, typically having a plain frieze, decorated by subtle bands of egg-and-dart decoration.

The Corinthian is by far the most ostentatious of the three main orders: in the hands of Roman architects, virtually every available space was encrusted with some form of decoration. Here the columns are typically of Ionic proportion, in terms of width relative to height, with elaborately carved acanthus-leaf capitals. Unlike the plain Ionic frieze, the Corinthian frieze is typically covered with elaborate sculptural decoration (see Sutton, p. 373). (It should, however, be pointed out that in practice these strictures were often rather more loosely observed that sources such as Vitruvius would have us believe.)

Individual activity: The temple of Hera and the Parthenon

Sutton compares the (Doric) temple of Hera at Paestum (illustrated on p. 11), with the Parthenon in Athens (illustrated on p. 12), in the following terms: ‘the Parthenon ... employs the same optical subtleties as the Paestum temple, but in a more refined form’.

Look closely at the images of the two temples in Sutton, and also at the photographs of the temples below…

Try to say in what respects they differ architecturally (remember, they both utilise the same order, Doric). Why is it that Sutton describes the Parthenon as being the more 'refined' of the two?

Record your answer in your notes. At the end of the week, compare your answer with the sample answer sent to you by your tutor. How does the comparison alter your views on the questions?